close window

MedicineNet.com for Health and Medical Information

Source: http://www.medicinenet.com/script/main/art.asp?articlekey=107502

Study Unravels Mystery of Dyslexia

Children With Dyslexia Can't Focus on Repeated Speech Sounds, Researchers Say

By Kelli Miller Stacy

WebMD Health News

Reviewed By Louise Chang, MD

Nov. 11, 2009 -- New research may provide an answer as to why children with dyslexia often have difficulty hearing someone talk in a noisy room.

Dyslexia is a common, language-based learning disability that makes it difficult to read, spell, and write. It is unrelated to a person's intelligence. Studies have also shown that patients with dyslexia can have a hard time hearing when there is a lot of background noise, but the reasons for this haven't been exactly clear.

Now, scientists at Northwestern University say that in dyslexia, the part of the brain that helps perceive speech in a noisy environment is unable to fine-tune or sharpen the incoming signals.

"The ability to sharpen or fine-tune repeating elements is crucial to hearing speech in noise because it allows for superior 'tagging' of voice pitch, an important cue in picking out a particular voice within background noise," Nina Kraus, director of Northwestern University's Auditory Neuroscience Laboratory, says in a news release.

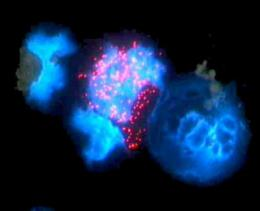

The brainstem is the first place in the brain to receive and process auditory (hearing) signals. It is supposed to automatically focus on the information, such as repeated bits of speech, and sharpen it so you can discern someone's voice from, say, the noise of a chaotic classroom. The new study, however, provides the first biological evidence that children with dyslexia have a deficit in this auditory process. As a result, the brainstem cannot focus on relevant, predictable, and repeating sounds.

The new evidence is based on a brain activity study of children with both good and poor reading skills. The children wore earphones that repeated the sound "da" in different intervals while watching an unrelated video. The first time, "da" repeated over and over again in a repetitive manner. In a second session, the sound "da" occurred randomly along with other speech sounds, in a variable manner. Electrodes taped to each child's scalp recorded the brain's response to the sounds.

The children also underwent standard reading and spelling tests and were asked to repeat sentences provided to them amid different noise levels.

"Even though the children's attention was focused on a movie, the auditory system of the good readers 'tuned in' to the repeatedly presented speech sound context and sharpened the sound's encoding. In contrast, poor readers did not show an improvement in encoding with repetition," Bharath Chandrasekaran, one of the study's authors, says in a statement.

The tests also revealed that children without dyslexia were better able to repeat sentences they had heard in noisy environments. However, the researchers noted enhanced brain activity of the children with dyslexia during the session when the "da" sound was variably played.

"The study brings us closer to understanding sensory processing in children who experience difficulty excluding irrelevant noise. It provides an objective index that can help in the assessment of children with reading problems," Kraus says.

The findings, which appear in this week's issue of Neuron, may also help teachers and caregivers devise better strategies for teaching children with dyslexia. For example, the study authors say children with dyslexia who have trouble sorting out voices in noisy classrooms may benefit simply by sitting closer to the teacher.

SOURCES: Chandrasekaran, B. Neuron, Nov. 12, 2009; vol 64: pp 311-319.